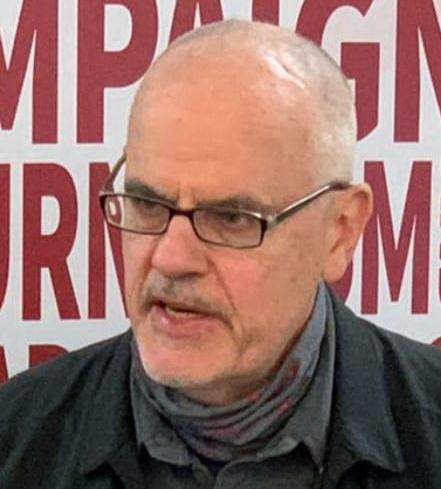

By Tim Anderson, on one side of his family history which shows how European immigrants gained land and social mobility at the expense of indigenous Australians.

You would have difficulty finding Glendhu (Scotland) on a map, and Google will probably give you a place in New Zealand or a B&B in Scotland. There is no village at all by that name in the twin fjord valleys of Glendhu and Glencoul, in the far north west of Scotland.

However one set of my great-great-grandparents named their Tasmanian farm ‘Glendhu’, having emigrated to Australia in the early 19th century from the small farming communities around Scotland’s Glendhu. Tracing their history provides an amazing link between the highland clearances of Scotland and the lowland clearances of Tasmania.

In 1995 along with two of my cousins I went to Tasmania to look for the old farm house called ‘Glendhu’, near Ouse. Teenagers James Clark and Jane McKenzie had emigrated to Tasmania in 1825, looking for land to raise sheep. Governor Arthur was giving away land to such emigrants, provided they could show they had the means (at least 500 pounds) to ‘develop’ that land. It took James and Jane several years to show they had access to this sort of money.

At that time there was a ‘low level skirmishing war’ between the colonists and the local Aboriginal people, who found their valley progressively occupied. While Arthur ‘gave’ the land to colonist families, they were required to be sworn in as ‘special constables’, often assisted by paroled convicts, to assist in this war. There were regular spearings of sheep and settlers, and reprisal killings. The problem for the indigenous population was that, for every settler eliminated, another boat would arrive with hundreds more.

Very soon after my ancestors acquired their land, Arthur launched a great ethnic cleansing operation called ‘The Black Line’, in October 1830. The aim was to herd all the indigenous people from the east coast of Tasmania down into the Tasman peninsula, and there lock them into some sort of concentration camp. Historian Lyndall Ryan says there were in fact several operations over 1830-31 and, while the concentration camp did not eventuate (instead, the ‘model prison’ at Port Arthur was created), the operations ‘ended in the forced surrender of the Tasmanian Aborigines’, who were then relocated to the Bass Strait islands. It is almost certain that my grandparents took part in, and directly benefited from, these ‘Black Line’ operations.

The October 1830 ‘Black Line’ – the colony attempts to corral Aboriginal people on the Tasman Peninsula. Lieutenant-Governor George Arthur ordered thousands of able-bodied settlers to form what became known as the ‘Black Line’, a human chain that crossed the settled districts of Tasmania. The line moved south over many weeks in an attempt to intimidate, capture, displace and relocate the remaining Aboriginal people. The plan failed in the short-term but it ultimately allowed Europeans to take control of the region. From the National Museum of Tasmania.

Only a few years earlier, their own families had been evicted from small farming lands on the west coast of NW Scotland. The Highland clearances were carried out in the wake of the consolidation of British power over the highlands in the mid 18th century, where a privileged aristocracy first ‘enclosed’ previously common lands, then forcibly evicted thousands of small farmers from their small and marginal plots. There was resistance, slaughter, burnings of houses and later resigned abandonment. Historian Eric Richards says ‘communities were finally erased and their people dispersed’. In Sutherland between 1807 and 1821, ‘thousands were cleared … and replaced by great sheep farms’ run by wealthy graziers. Richards says the final 1821 clearances in Sutherland ‘were executed at the point of a sword’. Much of Sutherland County remains depopulated, to this day.

These ‘crofters’ had been allocated up to 3 hectares per family. They ran sheep, grew vegetables, caught fish and harvested seaweed. Some still survive today. At Kylesku, on the shore of the twin fjord (saltwater) lochs Glendhu and Glencoul, a girl working in the local pub told me the crofters at nearby Unapool (not to be confused with the much larger port village of Ullapool, farther south) still provide that pub with much of its food. These crofters live in a tiny settlement of houses perhaps 100 years or more old, alongside the ruins of stone houses more like 200 years old. These are the vintage of my great-great-grandparents. On the north shore of Loch Glendhu I could see no old crofters’ houses, but rather some more upmarket country houses alongside hydro and forestry schemes. An old man at Scourie, a bit further north, told me that there had been McKenzies as crofters at Unapool, until 10-12 years ago.

Contrary to the patri-nomial tradition, Jane’s family name McKenzie survived longer than that of her husband, because the McKenzies had greater importance, in clan terms, than the Clarks. Consequently my grandmother was Elsie McKenzie. Though she left Tasmania for New South Wales, her family seems to have dragged themselves out of their status as dispossessed rural peasants to a more or less middle class existence, so that Elsie was a school-teacher at the beginning of the 20th century. Much of this was due to the extra capacity from her family’s good farming land, gained at the expense of another people.

It is one of the cruel ironies of history that this branch of my family, themselves victims of a cruel dispossession had, in not much more than a decade, restored their fortunes by taking part in the brutal dispossession of another people.

———–

Lyndall Ryan (2013) ‘The Back Line in Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), 1830, Journal of Australian Studies, Vol 37, No 1

Eric Richards (2008) The Highland Clearances, Birlinn, Edinburgh